Removing Child Soldiers’ Scarlet Letter: ‘Body Mapping’ and ‘PhotoVoice’ help reintegration

By Julia Boccagno

“You are nothing.”

“You don’t deserve life.”

These are the words former child soldiers live with daily in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Since the Second Congo War ended, over 31,000 underage combatants have been released from non-state armed militia groups. Besides experiencing immense physical and psychological trauma, former child combatants return home to be treated with hostility and mistrust by community members–leading some to rejoin the military rather than face social isolation.

Using new revolutionary techniques, researchers of the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative (HHI) and of the Eastern Congo Initiative (ECI) partnered with six Congolese community groups to improve future reintegration programming for former underage combatants and at-risk teenagers. At our latest Washington Network on Children & Armed Conflict (WNCAC) forum, both organizations presented Innovative Participatory Research with Former Child Soldiers in Eastern Congo.

“You live in difficult conditions, have difficulties in eating. You have no job, you start envying people’s belongings,” explains a former male soldier from Uvira. “You remember that in military life, you were looting civilians, and you could have something to eat. Now, you regret the causes which pushed you to leave military life.”

In response to the situation, HHI and ECI decided to include the affected children into the research process. Using techniques known as “Body Mapping” and “PhotoVoice,” researchers not only gathered information for future reintegration methods, but were also able to give the former child soldiers a sense of independence and control for the first time.

During each Body Mapping session, a facilitator presented each participant with a large piece of paper with the outline of a person traced on each. Moderators then purposefully asked  each former child soldier a series of open-ended questions to facilitate visual storytelling. One example of a question asked was, “What is the effect of being an underage combatant on a child’s head?” Participants would then literally draw out an answer on the Body Map. At the conclusion of each session, the Body Map displayed a “map” of seen and unseen effects.

each former child soldier a series of open-ended questions to facilitate visual storytelling. One example of a question asked was, “What is the effect of being an underage combatant on a child’s head?” Participants would then literally draw out an answer on the Body Map. At the conclusion of each session, the Body Map displayed a “map” of seen and unseen effects.

The results of this research method illuminated the psychological and physical trauma that former combatants encountered. One former female child soldier described her Body Map:

“Her eyes have seen bad things: people dying and being raped. Her nose has smelled the dead people and her ears have heard the bullets crackle and the large missiles of war. Her mouth has eaten bad food, but does not talk.”

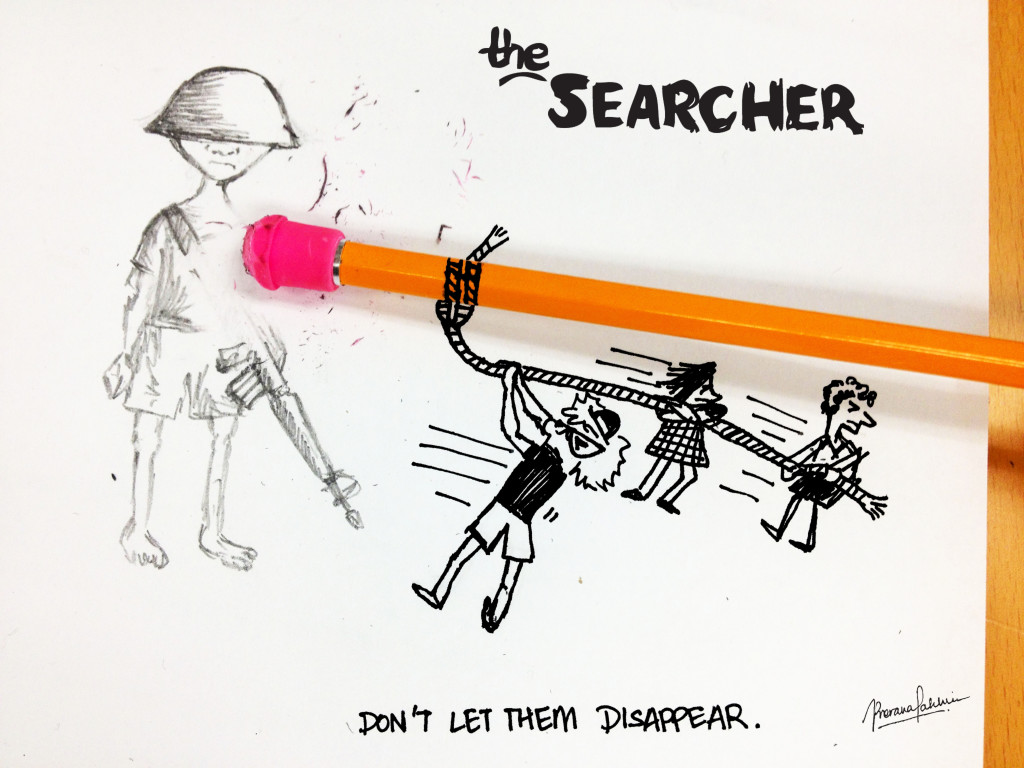

In addition to Body Mapping, HHI and ECI collected data using PhotoVoice, a method that visually represents the emotional, physical and psychological effects of a particular event. Participants were given a camera and asked to chronicle their own story with whatever image they feel best captured their experiences. Researchers were astonished at the depth of reflection and symbolism expressed through the photos, allowing them to learn about a child’s life before, during, and after being a soldier.

PhotoVoice. A child soldier’s explanation: Similar to this tree, former child soldiers are left without support, abandoned by their communities and in the process of disappearing.

After both the Body Mapping and PhotoVoice sessions, the researchers created a “Mobile Museum” that traveled to various schools and churches throughout Congolese communities. The public display of the raw and hidden struggles of child soldiers through the Body Maps and PhotoVoice images generated a sense of solidarity. Former child soldiers realized they were not alone in their challenges; while community members better understood and empathized with the complex hardships of former child combatants.

A community leader from Goma expressed that progress is already in the works:

“When a child goes to military life here in Africa, it means you have lost him, because we consider military life as a place of hooligans… but when he comes back home, you treat him as a human being. He can be a man in the future.”

To view the full “Innovative Participatory Research with Former Child Soldiers in Eastern Congo” presentation, click here.

____________________________

As a rising American University junior, Julia Boccagno majors in Broadcast Journalism and double-minors in International Studies and Italian with the hopes of becoming a future foreign correspondent. She firmly believes that objective news reporting is a vital tool within the peace and conflict resolution conversation. She is currently the New Media Intern at Search for Common Ground.